Leading through disruption requires a special kind of leader. Today’s leaders must not only be proficient in change management, but also conscious of their own cognitive biases so they can interpret data and the mood of their team accurately.

Leaders can become their own worst enemy when working with or leading a team. In approaching new plans, projects and strategies, cognitive biases prevent us from seeing situations clearly. We overvalue some data points while undervaluing others.

To avoid the most common cognitive biases, we must be conscious of them and learn to harness mental shortcuts effectively. These three biases are likely impacting your work and leadership style:

- Confirmation bias occurs when we digest new information to confirm existing beliefs or theories, even when the new information contradicts those theories. Because our convictions are so strong, it is difficult to tear down a belief—even when proven false. Since infancy, we are more inclined to engage with things we like than with things we dislike. As a result, we seek out and retain more information that supports our current beliefs. One study proved that even when given data on why a subject’s belief was false, that subject ignored information contradictory to his or her view and walked away with convictions stronger than before.To counter this tendency, seek additional opinions and perspectives. Gather a diverse team to review your conclusions, and ask someone to play devil’s advocate. If that isn’t possible, analyze the problem from a different point of view and evaluate all data with equal rigor.

- Overconfidence has plagued everyone at one point or another. For instance, 90% of Americans believe they are above-average drivers—a statistic that clearly cannot be supported by data. We often place too much confidence in our abilities, knowledge and opinions. We overweigh our contributions when they are not based on fact, or “trust our gut” when we should consider the situation as a whole.To better evaluate problems, assess where your information is coming from—facts or a gut feeling? What data can confirm our information is up-to-date? Who else helped you gather the information? Did they go through a fact-finding methodology to ensure accuracy? Once you’re sure your information is factually accurate, ask for second opinions.

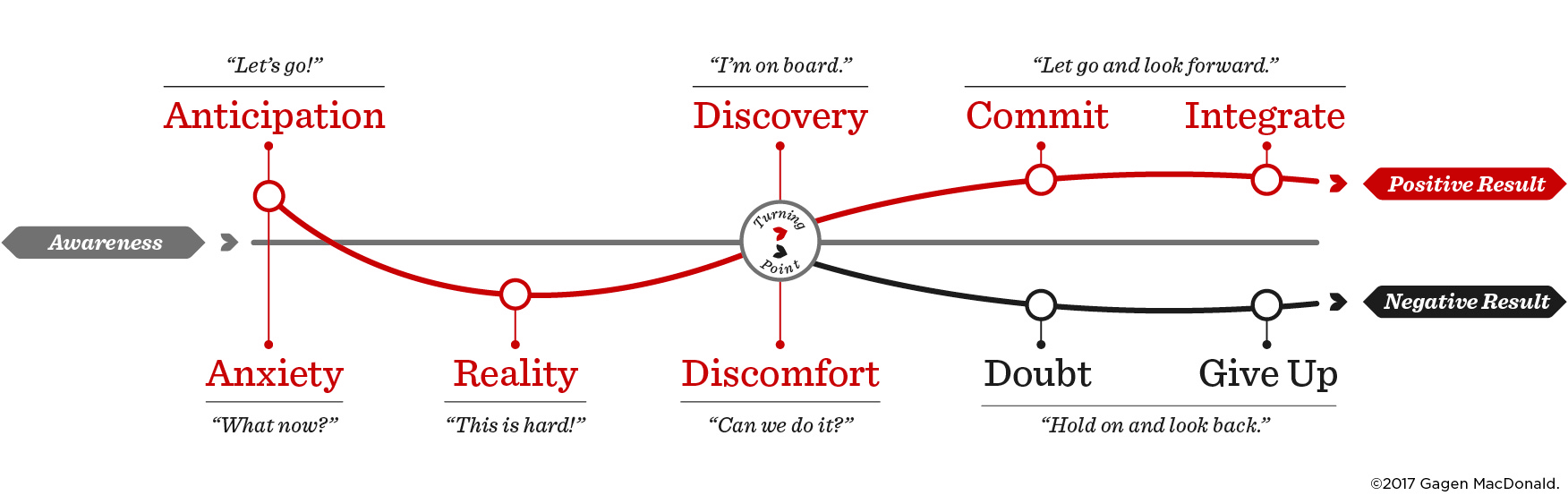

- Fundamental attribution error (FAE) is another common bias. Psychology Todaydefines the term: “When we see someone doing something, we tend to think it relates to their personality rather than the situation the person might be in… Closely related to the FAE is the tendency we all have to take things too personally.”When involved in a project, leaders and employees often oscillate between anticipation and anxiety. These shifts in attitude can radically change the odds of success and scramble our ability to attribute problems to the true cause.Let’s face it: change is hard. In the heat of the moment, it’s not uncommon to focus on failure instead of recognizing it as a necessary step in lasting change.Failures rarely arise from a single cause, and objectively analyzing the factors that led to a failure is a necessary part of failing forward. At Gagen MacDonald, we refer to the progression in attitudes as the change momentum curve, and it’s a useful tool for understanding the role of the leader.

Instead of blaming the opposition or perceived deficiencies in the team, it’s the leader’s job to help the team see failure as part of the overall change journey instead of as an isolated incident. It’s up to leaders to shift the momentum back to positive attitudes and behaviors and to reshape thinking so that employees are open to discovery. If leaders can correctly identify points of failure, they can take steps to improve—learning from past mistakes, rather than jumping to the wrong conclusions.

Instead of blaming the opposition or perceived deficiencies in the team, it’s the leader’s job to help the team see failure as part of the overall change journey instead of as an isolated incident. It’s up to leaders to shift the momentum back to positive attitudes and behaviors and to reshape thinking so that employees are open to discovery. If leaders can correctly identify points of failure, they can take steps to improve—learning from past mistakes, rather than jumping to the wrong conclusions.

Our decisions are often based on heuristics—mental shortcuts that enable us to function efficiently and quickly. These shortcuts aren’t all bad: leaders can harness heuristics to motivate their teams, and mental shortcuts can help us act quickly under pressure and with success. But sometimes, biases lead to larger mistakes that can easily be avoided by evaluating outcomes and decisions objectively to make sure we’re listening to facts rather than instinct.

Learn more about shifting leadership mindset and the vital role committed leaders play to stay ahead of disruption in our eBook The Three Things That Change Everything™.